Rare Photographs of Black Beauty Pageants Offer Insights into 1970s London

ARTSY EDITORIAL

BY CHARLOTTE JANSEN

JUL 5TH, 2016 4:21 PM

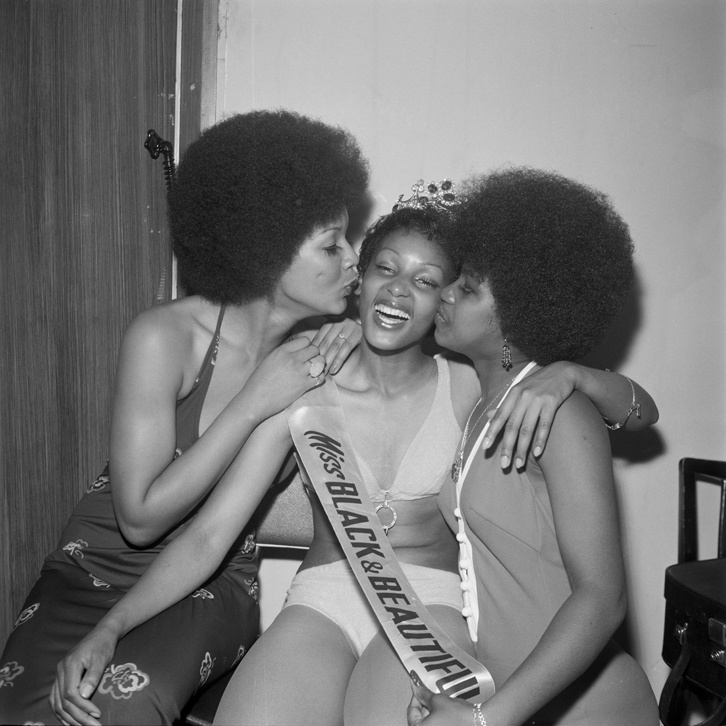

Raphael Albert, Miss Black & Beautiful Sybil McLean with fellow contestants, 1972. © Raphael Albert/Autograph ABP.

In the 1970s, the leafy suburbs of West London were home to a thriving mix of people; large populations from Ireland, Poland, South Asia, and the Caribbean all converged there. In the Hammersmith area, a vibrant West Indian community was establishing itself, and it was in this context that Grenada-born photographer Raphael Albert began to work for a number of black British newspapers, including the West Indian World, which sent him on a pivotal first assignment—covering the Miss Jamaica pageant for the paper’s London edition.

Over the next three decades, Albert would play a unique role in supporting the Afro-Caribbean community in Britain through organizing his own franchise of black beauty pageants in West London. Dubbed the Miss Black and Beautiful contests, many took place at the legendary dance and music venue Hammersmith Palais. An unprecedented exhibition of Albert’s work—which has not been properly contextualized until now—opens this week at Autograph ABP’s Rivington Place gallery, featuring 60 photographs from the 1970s that were drawn from the late photographer’s extensive archive.

|

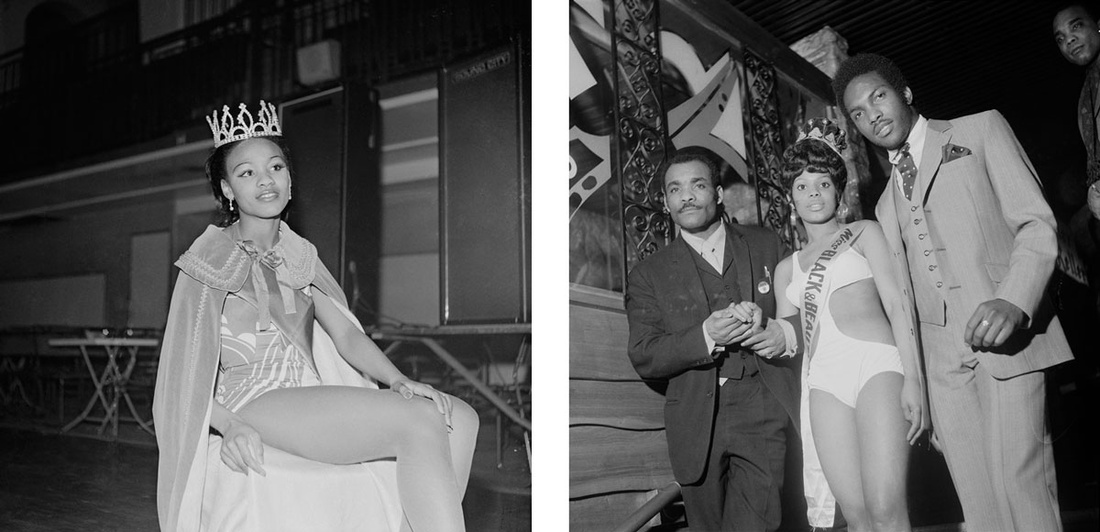

Left: Raphael Albert, Holley posing at Blythe Road, early 1970s. © Raphael Albert/Autograph ABP. Right: Raphael Albert, (unidentified) Miss West Indies in Great Britain contestant posing at Blythe Road, 1970s. © Raphael Albert/Autograph ABP.

Renée Mussai, Curator and Head of Archive at Autograph ABP as well as the curator of “Miss Black and Beautiful,” has been working with Albert’s archive since 2011. She emphasizes the value of Albert’s work at the time: “Not only did the pageants offer the opportunity to create a distinct space for Afro-Caribbean self-articulation—a wager against invisibility, if you will—they also responded to contemporaneous mainstream fashion and lifestyle platforms where black women were largely absent, or at best, marginal.” Albert’s dual role as producer and documentarian of these events points to the ongoing importance of photography in the construction of social identities and self-representation. “These spaces existed simultaneously and cross-fertilized Albert’s converging interests in the promotion of black beauty and providing areas to help young black women build confidence and become more visible,” Mussai notes.

The lack of representation and acknowledgement of black beauty was widespread among pageantry at the time. In the Caribbean, Mussai points out, pageants had been organized since the 1930s, yet in the U.K. there were no contests for black women. Meanwhile, in the U.S., “the notorious rule number seven prevented black women to enter mainstream pageants for decades, and it was not until 1970 that a black woman was represented in the Miss America contest,” Mussai tells me. “The first black African Miss World winner was crowned in 2001; and Miss Universe has had less than five black winners in over five decades.” Albert was an enterprising young man who saw the potential for pageants to serve as a platform for expression, performance, and celebration of black women—an alternative to the dominant Eurocentric beauty ideals disseminated in mainstream media, fashion, and entertainment industries of the day. Because images representing black beauty and culture were scarce in Britain, Albert became revered and respected in his community. Today, his prolific practice offers rare insights into the social evolution of the black community in Britain.

|

Left: Raphael Albert, (unidentified) beauty queen, 1970s. © Raphael Albert/Autograph ABP.

Right: Raphael Albert, (unidentifed) Miss Black & Beautiful escorted by two men, 1970s. © Raphael Albert/Autograph ABP.

Crucially, Albert’s images also give us a positive vision of a jubilant and vivacious black British community. “Refreshingly, there are no signs of displacement or marginality, nor a sense of alienation in Albert’s portraits—his pageant images offer a different, and perhaps lighter, form of cultural resistance,” Mussai says. Yet all was not as blissful as it appears. In multicultural communities of West London in the ’70s, racism was prevalent, frequent, and ugly. “Albert’s photographs of the late 1960s and early ’70s were taken at a time of ‘No dogs. No blacks. No Irish,’ in a country irrevocably tainted by Enoch Powell’s 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ anti-immigration speech, delivered only three years after the introduction of the 1965 Race Relations Act, the first legislation passed in the U.K. to outlaw racial discrimination on the grounds of color, race, or ethnic or national origins,” Mussai notes. With the recent spike in racially motivated hate crime in post-Brexit Britain, Albert’s images reinforce the history of immigration and its resounding significance.

The portraits are a compelling record of the positivism of a liberal new generation of Britain in the 1970s. And although Albert’s work—until now—has been rooted in its local impact, “Miss Black and Beautiful” traces the photographer’s place in the global campaign for black beauty, fashion, and creativity, and initiatives that continue today. “I tend to think of the ‘Black Is Beautiful’ movement as a byproduct of the American civil rights and black power movements of the1960 and ’70s, that naturally spread from the U.S. across the so-called ‘black Atlantic’ into a global consciousness,” Mussai says. “For us it is absolutely crucial to see these pageants as ‘of their time’—it was about ‘owning’ the idea of beauty, about occupying a space that has historically negated black women an existence within its terrains.”

—Charlotte Jansen

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário